Highlights from Open ENLoCC President Giuseppe Luppino’s speech at the webinar organised by Scandria®Alliance

In the near future, the number of cities classified as urban nodes could increase from the current 88 to over 420. This change is part of the revision process of the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) guidelines and will inevitably entail new challenges for cities all around Europe. These include the need to efficiently and effectively manage urban logistics and last-mile deliveries, the cause of much urban traffic and pollution in urban areas.

For this reason, the Scandria®Alliance task force dedicated to urban nodes studied the perception of possible commitments required among existing and potential urban nodes along the ScanMed corridor. The results were discussed on Friday 1 December during the webinar “Navigating the future of urban node”, which was also attended by Open ENLoCC president Giuseppe Luppino.

In his speech, Giuseppe Luppino focused on the approach of the Emilia-Romagna region (Italy) to sustainable management of urban logistics, giving as an example some of the most innovative projects implemented in the Italian region, including the GRETA project, an EU Project funded by the INTERREG Central Europe and in which Open ENLoCC is a partner. GRETA project aims to decarbonize the last mile delivery in Central European Functional Urban Areas (FUAs) by implementing joint sustainable solutions. One of GRETA’s pilot actions is Reggio-Emilia, an Italian city located in the Emilia-Romagna region, where last-mile delivery modes with zero-emission vehicles and cargo bikes will be tested, reorganising urban spaces with the application of curb management to achieve sustainable last-mile delivery. As mentioned, in fact, the management of the last logistics mile is a key element in reducing pollutant emissions in urban areas and thus in achieving the challenging climate neutrality targets set by Europe.

“Normally, historic city centres are those parts of cities that are mainly the target of city logistics regulations – explained Luppino -, but now we are also targeting the extra urban areas, where there are some business-to-business and business-to-consumer flows that in many cases are not optimised. We must also consider that the historical centres and urban contexts of Italian cities, and almost all medium-sized cities in Europe, have a limited capacity in terms of roads and public spaces with high competition between road users and commercial activities. Urban freight distribution is fundamental for the commercial activities, for restaurants and for the life of a city – Luppino continued -, but today there are different challenges, although there are also new solutions and new technologies that allow a higher level of innovation. Public administrations have always developed regulations on city logistics, but in different eras the approach has been very different. Unfortunately, the issue of urban deliveries is addressed by public administrations in Europe with a lack of adequate communication between them and transport operators.

The challenge with this distance arises from a divergence in perception regarding the actual impact of measures by public authorities, which significantly differs from the perspective of the commercial sector. This discrepancy is a key reason why current planning may not be adequately prepared for the trends already unfolding in our cities.

So, how can we address this issue? Luppino cited the city of Bologna as an example, where the first Sustainable Urban Mobility Plan was formulated at the functional urban area level. Notably, this plan incorporated a dedicated chapter for the Sustainable Urban Logistics Plan, thanks to the SULPiTER project.

However, the prevailing situation in most cities remains marked by significant inefficiency. There are primarily two issues that need attention: firstly, the challenge of last-mile delivery vans operating without full loads, and secondly, the problem of limited public space allocated for logistics.

Luppino explained, ‘All users routinely occupy the same spaces simultaneously. Public areas are now congested with parking lots, cycle lanes, bus routes, charging stations, and curbside management, presenting a major challenge in our cities. There is insufficient space for deliveries. Both of these aspects need to be addressed, and it is precisely these issues that the GRETA project is focusing on. The objective is to redefine delivery methods as alternatives to last-mile van deliveries. This is crucial because our cities have numerous delivery points, and the surge in eCommerce has significantly impacted urban delivery traffic.’ Hence, there is an urgent need to study and implement alternative solutions.

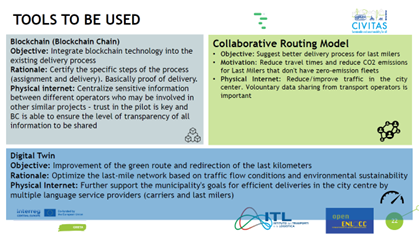

Tools such as Blockchain, Digital Twin and Collaborative Routing Models that enable better planning for operators and public administrations are some of the solutions being worked on.

Furthermore, Luppino highlighted the fact that “decisions at the global level can also influence the urban freight distribution. However, the opposite is also true: decisions at the local level can have global repercussions in the context of urban freight distribution”. For example, a city’s decision to invest in an efficient public transport network can help reduce freight traffic in urban areas, reduce air and noise pollution in cities, improve air quality and public health, improve road safety and transport efficiency. Furthermore, a local government’s decision to promote the use of electric or low-emission vehicles in goods distribution can help reduce overall greenhouse gas emissions. Finally, a freight transport company’s decision to use sustainable logistics practices, such as route optimisation and waste reduction, can help reduce the environmental impact of goods distribution.

However, what is lacking today to achieve the desired results? The answer is in the data. “Road users have conflicting needs: the acquisition and sharing of purpose-driven data allows for a proper understanding of how public and private space is used, how cities should regulate themselves while ensuring sustainability, safety and supply chain efficiency. Furthermore, local authorities and urban planners need to flexibly design, measure, evaluate and manage urban space, in collaboration with service providers, technology and business model innovators, actros and local/governmental communities; but to date – Luppino concluded – unfortunately, urban logistics still does not provide sufficient data. It is therefore crucial to establish the right governance to lay the foundations for a data economy that people and businesses can trust, taking into account real-time demand priorities”.

Highlights of the speeches by all webinar participants are available on the Scandria®Alliancewebsite by clicking here.

Sources:

- GRETA Project: www.interreg-central.eu/projects/greta

- DISCO Project: www.discoprojecteu.com

- URBANE Project: www.urbane-horizoneurope.eu

- The last-mile delivery challenge Report, Capgemini Research Institute: www.capgemini.com/insights/research-library/the-last-mile-delivery-challenge